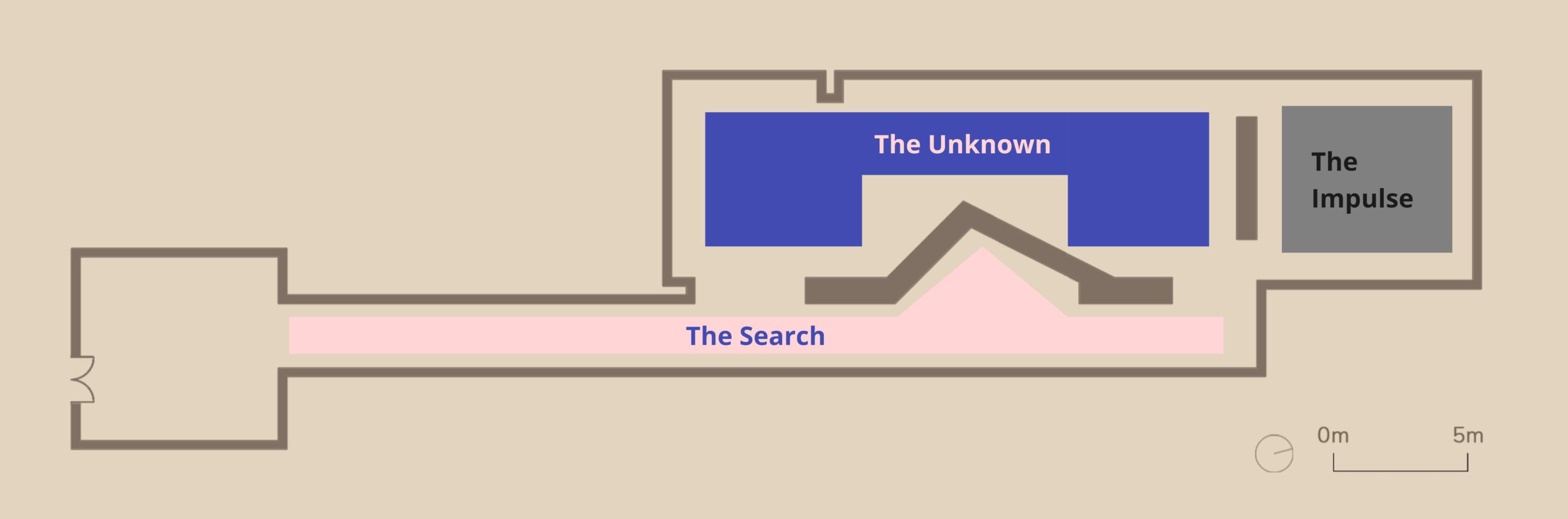

The Search

Delia uses ceramic test pieces and scale models as her “notebook”, exploring shapes, textures, colours, and compositions. The selection of works in this section includes everyday elements like Christmas trees and face masks, examining their appearance, historical associations, and potential significance. In the exhibition, her objects are organised to reveal connections and intuitions, including scale models of her public art commissions. She challenges clay’s properties by integrating materials like salvaged bricks, roof tiles, and her grandmother’s weaving. Collaborating with material science researchers, she incorporates graphene into Kaolin clay. Delia continuously expands her visual vocabulary, engaging with her materials’ history and contexts.

The Pursuit for Dynamism

“Looking inward, I know myself to be a dynamic and extroverted person.”

Kenneth Tay:

I also found it interesting when looking at that catalogue and reading the poem that you emphasise a lot on evolution, on relationship, on growth, renewal. For example, I think there was a work in that exhibition, Row (1982), which has seed-like porcelain pieces arranged in a row. And each slowly turns at a gradual angle away from each other. So, you can obviously see the flow of time. And it somehow reminded me of this kind of slow and imperceptible changes in nature. that we sometimes do not even see in our lifetimes. So, in short, that kind of a sense of time that is maybe much deeper and rooted in nature. And I wonder, maybe as a provocation to you – does nature for you maybe exist in a kind of plastic form? And what can we understand through thinking about this?

Delia Prvački:

Looking inward, I know myself to be a dynamic and extroverted person. Reflecting upon the artwork that I was producing at the time, they were polished, abstract, and poetic. The artworks were much more of an extension of the school of art that I came from, rather than a reflection of my personality. Nonetheless, I also consider myself to be a restless and curious person, hence these artworks were still satisfactory. Despite that, I keep finding myself unsatisfied and consistently desiring to add more to my work. I do not feel content with a mindset such as “This is a shape; this suffices and should stay this way.” Thus, I started incorporating movement into the forms of art that I created.

Once, I created a set of 12 to 15 pieces of artwork in moulds, and I “intervened” each mould to create dynamism and movement in its form. The interventions I made were either on the plaster mould itself before the casting in the mould or on the artworks in the moulds. And this is the reason why Row is a set of 12. Each piece in the set of 12 is a finished front. Whenever I display this piece, I always display them akin to the opening of a fan, and thus create dynamism and movement. There is an energy in such display, albeit quiet and still.

All of this came about because I was dissatisfied and unhappy with my artwork being simple monotonous shapes, and thus I created a series of artworks which featured movement.

Translating the 2D to the 3D

“I became intrigued in the ways I can navigate across dimensions.”

Kenneth Tay:

When we spoke, you told me that when you think about the potter’s wheel – the turning, the circle itself, how one looks makes the movement – it’s kind of like nature itself, the seasons.

Delia Prvački:

Yes, it’s like nature. A little mystical, hypnotic and like a dervish dance. It is a moment, and it is part of the production process. I have seen this movement so much that I have gotten used to it. However, I still wanted to make art out of the movement. After I became a professionally practising artist, I decided that the movement of the pottery wheel was going to be my first source of inspiration for my artwork. I sought to translate that instance of the moving wheel, its action and aesthetics to a three-dimensional (3D) object.

While translating that moment, I became intrigued in the ways I can navigate across dimensions. From 2D objects I was able to sculpt 3D objects, and from 3D objects I flattened them into 2D with the texture of its original three-dimensional form. As such, I like to describe my work as “volume that has a skin.” I treat the surface of 3D objects as its skin, and I never treated them with the aims of decorating them.

On Prvački’s Public Art

“Every time I’m making public works, I feel like I bear a very serious responsibility. This is because there are a lot of factors to be considered in the work, for example the building structure, the architecture, the surrounding environment, the building’s functions, the passing traffic, and the way that people interact with the building. Hence, I feel very privileged and honoured if I were given a chance to make public art.”

Kenneth Tay:

Speaking about artworks that you produce as part of commissions that eventually get dismantled or stored away – I think that the work that you did for the Singapore Power Building in 2001 remains quite an exceptional piece to me based on the documentation that you shared. I think this was because from the beginning, it was conceived to be, as I understand it, partially submerged in water. So, it was part of this public water feature that people would walk through. It brings to mind a lot of things like hydropower. But as you mentioned earlier, this is a city that is built from water life. Could we spend a little bit of time talking about this work, what you were thinking about when you were commissioned to do it, and because I find it so interesting that water comes back to your practice in very different, but also very interesting ways.

Delia Prvački:

In 2000, the time between the commissions for Suntec City and the Singapore Power Building, I have had experience in working for commissions and exhibitions. And by that time, several of my projects had involved water, with one of the earliest instances being the Danube project while I was in Europe.

However, the Public Utilities Board (PUB) project holds a special place to me. Its special place started out as an approach from the designer who was commissioned to renovate the building. This project was supposed to be handed over to its initial designer, who was a Japanese architect who won numerous awards for this project. There were also plans to revive unfinished plans for a pond on the concourse. The existing facade cladding was also done by the designer.

The commission came with 6 locations – 2 places on the main concourse facing Somerset Road, 2 places behind Devonshire Road, one at the corridor in between, and one on both sides of the lift lobby. There were plans for a cascading wall of water going over the mural in the lift lobby too.

After some preliminary research, I found the architecture plan and started to develop my work around it. The architecture of the building had a symmetrical beauty which I was fond of. Thus, my idea was to respect the existing architecture and work around it to explore the possibilities of where to integrate my work. The artwork that I produced aimed to harmoniously blend into the wall. It was constructed with features of water, and the effect of a carpet that emerges from the wall and submerges into the water. I treated this piece not like commissioned work, but rather something to just fill up the space.

I took this piece very seriously. It is also the project that I liked the most. This piece of work is meaningful and conceptual because it evokes ideas of power, supply and the Public Utilities Board. The idea of “energy and flow” is central to this piece of work. While working on this piece, I was intrigued by the idea of how the energy we consume is transported to us. An example would be the way that water is used to power the electrical energy that we consume. This idea could be poetically and artistically translated into a critique of our dependence on energy supplies.

Expanding on the idea, I integrated the water features with nature by having fishes swim between the artworks. The artwork was made of several pieces, which had a common visual language and logic. This decision was a unique and special opportunity for me. Whenever I talk about it, I feel sad and regret that this piece of art doesn’t exist anymore.

Every time I’m making public works, I feel like I bear a very serious responsibility. This is because there are a lot of factors to be considered in the work, for example the building.

The Unknown

Delia explores the connection between clay, the environment, and natural resources, addressing themes like history, geopolitics, capitalism, colonialism, and craftsmanship. Using materials, equipment, images, and stories related to resource exploration and extraction, she creates complex ceramic sculptures. Her works draw from history and mythology, like 1830s terracotta roof tiles linked to colonial trade and the Greek myth of Cornucopia, symbolising abundance and sustainability. Delia’s art includes assemblages, mosaics, glazing, and staining, often presented as installations or site-specific sculptures. This selection showcases her works from earlier exhibitions, highlighting her diverse interests and methods, including pieces from 1998 and 2021.

Silk Road

“I very much wanted to show something that could connect Southeast Asia with Venice.”

Kenneth Tay:

In 2007, you had two shows that were back-to-back that relate to this topic, the first being “Compass” held in Piran, Slovenia, and the second being ”Silk Road” in Venice, Italy. The exhibition titles managed to foster some interest as they point to navigation and the movement of people and goods in Europe.

Yeah, it’s great that you talk about metals and this whole movement of goods and supply lines. In 2007, you had these two shows that were almost back-to-back right, the first being “Compass” held in Piran, Slovenia, and the second, “Silk Road” in Venice, Italy. The exhibition titles are already interesting in themselves, because they point to navigation, the movement of people and goods in Europe.

In relation to those exhibitions, I found the concept of the artwork Silk Road to be very cute. The art piece is a huge circular piece of ceramic, and there’s a toy train covered in white silk that runs around the Silk Road. From my reading, this piece speaks to the conditions of the goods and supply line industries, minerals, and resources, but also about the transmission of ideas and cultures. I also found this piece to be very interesting, as it was experimental that you decided to use a toy train on your work.

Delia Prvački:

The version of the art piece that has the train was first installed in the show in Venice. When I exhibited the work again in 2014, I did it without the train and replaced the train and the track with a succession of earth. This earth was made up of residual powder and debris from previous projects. I biscuit fired these residual earths and dipped them in oxides of different colours, creating an entire range of colours that now fill up the train track that was part of the Silk Road piece.

The decision to change out the train was because of a three-day-long exhibition I did with Alan Oei at the OH! Open House. I showed the version with the train. It’s very large, comprised of 4 pieces that when put together, is about 5 1/2 meters. It was troublesome to move and install it for only three days and bring it back to the studio afterwards. At the time of the exhibition, I was expecting people to have a little more interest for the art piece, however it did not appeal to the masses which I found strange. This led to me deciding to change out the train. I did this work for an exhibition in Venice, and I brought it back to Singapore. I always thought this is a precious work because it was developed out of some kind of local patriotism to the place (Singapore). I was expecting a little more interest for it, but I found it strange that it did not have any appeal at the time. That was one of the reasons I changed the train. I very much wanted to show something that could connect Southeast Asia with Venice.

There was a lot of talk about the new Silk Road (China’s One Belt, One Road initiative) Although the Silk Road did not pass through Singapore, Singapore was definitely close to it, and its proximity was a contributing factor that led Singapore to develop as a trading centre and a port city. Developing on this idea, I thought of creating something that could connect different ends of the world to each other. It was also in line with a project I did after the Danube, it was about me having resided in Singapore for many years, going back to the location where I had my first exhibition in Slovenia under the institution, the Obalne Galerije Piran.

The Obalne Galerije Piran is a group of galleries that belongs to the coast. Since they invited me back for a show, I became very motivated and inspired to create a piece that could connect the two places. Venice, being the place where Marco Polo returned with goods such as silk, spices, and ornaments, from the Orient, there’s a lot of similarities that could be drawn to the Silk Road. More about the exhibition, this exhibition started out in Piran, a beautiful city on the Adriatic coast. I was given a space there from a 13th century Franciscan monastery. Surprisingly the space was perfectly intact! Everything from the stone to the wood to the doors! The interior courtyard was reserved for various functions including baptisms and ceremonies. After assessing the space, I decided to come up with a piece for all four corners of the courtyard. And this is how I developed the first stage of this project.

I also decided to leverage on the idea of a compass, as Piran has port where people who are on the nearby seas use compasses to orientate and navigate themselves all the time. After that, I moved the installation from Piran to Venice, where I also brought in a second piece of work, the Silk Road, which was specifically curated to connect Singapore and Venice. I would describe this piece like a succession of landscapes as seen through the transitions from the earthy colour to a vibrant colour. As a whole, you see a cohesive and complete piece, but if you look closely, you’ll discover a lot of hidden details, similar to the experience of travelling from one place to another.

Piece of Sky

“I believe that the sky is something that every human, animal and plant enjoys equally. The sky is not only for the privileged.”

Delia Prvački:

Milenko (Delia’s husband) and I went on a trip to the Northen Territory of Australia organised by Marjorie Chu in 1997, and on this trip, I found the source of inspiration for A Piece of Sky, No. 7 (1999). We were camping and when the night came, I saw the sky. I had the impression that the night sky was going to fall on me, the stars were so dense. They were close to each other in a 3-dimensional sense. You could feel the visual weight of the stars like they were falling, I felt like I could touch the stars that night. When I returned to Singapore after the trip, I immediately worked on the art piece, which was titled A Piece of Sky. It was first exhibited at a show that I named Fire at Kakadu at Majorie’s gallery. The first iteration of the A Piece of Sky series is currently in the collection of the Singapore Art Museum (SAM). The inspiration for the exhibition’s name was from the view I saw that night; the explosion of stars was like a fire in the bush of Australia. After Marjorie’s exhibition, I then donated this piece (A Piece of Sky, No. 7 (1999)) to NUS in 2014.

I believe that the sky is something that every human, animal and plant enjoys equally. The sky is not only for the privileged. Although now that I think of it, planetary conquests are increasingly a game of the rich. If we look at the moon, there even exists a lunar embassy and that there are lunar territories available for purchase! Anyway, coming back to the sky, it is something that we can enjoy, regardless of the time of day and weather.

The Poem, De Rerum Natura (1982)

“amoeba possible shape, beginning, seed, fruit, evolution

formation, development. avoiding coincidences

multiplication of content

the form that was part of a goal

continuity

persistence

line”

Kenneth Tay:

Yeah. And it’s also quite interesting that your show in 1982, right, your exhibition was called delia keramoplastika, in this gallery in Koper, which is in present-day Slovenia. And I think here for the first time when I was looking through the materials that you provided, in the catalogue for the 1982 exhibition that I saw that you’ve articulated the term De Rerum Natura in your exhibition brochure. And you wrote a poem or visual poetry for it. I was wondering if I could trouble you to read what you wrote and maybe help us understand why you write it, like translate it…

I would love to hear it in Serbian first.

Delia Prvački:

So, it’s:

ameba-moguca forma, plod, pocetak, evolucija uoblicavanje,

razvijanje. bezanje od slucajonosti,

umnozavanje vrednosti

forma koja tezi cilju

kontinuitet

postojanost

linija

Kenneth Tay:

How would we read that in English?

Delia Prvački:

I will attempt to translate it into English:

amoeba possible shape, beginning, seed, fruit, evolution

formation, development. avoiding coincidences

multiplication of content

the form that was part of a goal

continuity

persistence

line

On Mining

“I didn’t want the chains to be interpreted as enslavement. Rather, I wanted to emphasise chains as a material and a tool.”

Delia Prvački:

The mining industry greatly influenced the economy and the development of different industries. And funnily enough, everything in my town was called “The Miner” – the cinema, the hotel, the restaurant. It was all “The Miner”. This notion of mining is a part of our nature. I remember going out to nature with my family on the weekends and passing by the entrance of the mines. So, this period of my life is forever associated with mining because of the marks and vivid memories.

There was the Săsar river, whose name translates to “Should I jump?”. We had to cross this river to get to the city centre, and very interestingly, the river’s colour frequently changed because of the stones in it. It was a small and narrow river that flowed from the mines. Miners were always washing metals, which led to oxidation of the metals. There were visible remains of iron oxide on the riverbank. Furthermore, depending on the intensity of the mining during that period, the colour of the river would be affected. Thus, the colour would sometimes be the colour of Earth, or it’d be orange, red, or brown. In the winter, it was greyish because of the snow.

In Transylvania, there is a gallery that was built by the Romans over 2000 years ago after they conquered the province. The Romans wanted to conquer the region at the time because they wanted to build a bridge over the Danube. Back then, there was an architect named Apollodorus who built a famous bridge over the Danube. After building the bridge, the Romans went into the central regions of Transylvania to explore the gold and metals in the mountains.

There are remains of archaeological sites in the mountains. Even after thousands of years, mining remains a contentious issue in my country. There were numerous demonstrations that arose out of conflicts; however, the conflict persists today. The conflicts were not solved because after the revolution in December 1989, when Romania closed its chapter on communis, all the state-owned resources were destroyed instantly. The factories, ports, railways were immediately sold off to private firms. Even the mines, forests and villages were sold off after the revolution. People were revolted to see what happened to the mines in the mountain, the Roșia Montană, which is where the red in the Săsar river comes from.

This mine is very rich in ores, especially gold. It was sold to a Canadian company to develop it. As a result of the development plan, the mountain and villages would be destroyed, and people would be forced to relocate. The company had plans to change the mining process, which involves the use of a lot of dangerous substances that would pollute the environment, resulting in the destruction of nearby rivers, vegetation and soil. There were protests surrounding this and archaeological sites were destroyed. This was a painful experience for me, as I was from a mining region, and my grandfather was from a family of miners. Even though my grandfather educated himself and became an accountant and auditor, he always extended his help to the miners. Hence, mining activity and the notion of mines are very present in my conscience. I was worried about the situation in Romania. It was 2010 when I was listening to the radio while these were happening.

At the time, I was 60 years old, it was 12 years after my work at CHIJMES for the CV exhibition (1998). It was also the year 2010, the year of the metal tiger, and I was thinking about the ‘metal’ aspect of the tiger and how connects to mine, “That’s my mine”. And so, I found such a coincidence. I believe in coincidences, but I also believe there are some things which are given as they are. Not everything are simply just coincidences. Everything has a purpose and a connection and continuation to something. I decided to make this mining themed project. In a way, it’s dedicated to my grandfather and other families of miners.

The Impulse

Delia Prvački’s work is influenced by her philosophical and spiritual experiences. Growing up in Baia Mare, Romania, she was surrounded by picturesque landscapes and a vibrant community of craftsmen and artists, shaping her artistic sensibilities. Witnessing the impact of large-scale mining and living under Communist rule, Delia studied ceramics to avoid scrutiny. In Belgrade, she encountered contemporary concepts like keramoplastika. Her migrations from Romania to Singapore have evolved her political and ethical views, framed by motherhood and introspection. Inspired by Lucretius’s “De Rerum Natura” and Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass,” she celebrates the natural world’s primacy and continuous transformation.

Reflections on Maturing as an Artist

“I think it’s also more justified for me, as a woman to use terracotta to represent the passing of time and show the subtle changes that happens to people with time through gradations of mark and relief making.”

Delia Prvački:

I think every stage of producing art is a new process. Engaging with my work is a sign of life moving on. I can now understand how our personal lived experiences and their interactions with history translate through our artworks. I do agree that maybe other artists may not necessarily be translating this experience in their work, but this is an intrinsic part of me. My life, my experiences, my aesthetics, and my personality exist in my art. The work I did at each stage of life reflects a new conclusion and a new understanding, but ultimately it reflects my maturation.

Kenneth Tay:

Yeah, this is especially the case with the work Ageing, in that show.

Delia Prvački:

Ageing was made of clay without any glaze. I used a little bit of oxide at the end to enhance the very subtle and gradual change of tonality. But I chose to do it in terracotta because I was 48 years old at the time. When I was 36 years old, I had a show in Belgrade at the Museum of Applied Art. I presented a similar piece of work, but it was in a different shape and colour. It was mask-shaped and there were 36 of them, each had a gradual change in its design.

Another thing I learned when I came to Singapore was the Chinese horoscope. It was about understanding the cycle of the year when you were born, and how the cycle would repeat every 12 years. I had a show when I was 36, when it was the year of the tiger. Then I had a show when I was 48 and it was the year of the tiger again. I started to develop a liking for this kind of numerology and consider it in my work. I wanted very much to do a similar piece of work again because I was 48. However, I didn’t want to take the walls from Milenko because he was exhibiting his paintings and drawings on the wall. Thus, I decided to make a floor piece made from terracotta. The floor was black and the terracotta with the gallery lighting on it, made my work very striking.

It also has something to do with me as a woman. Terracotta and clay have associations with giving birth, and thus I thought it made sense for me, as a woman, to do this. I think it’s also more justified for me, as a woman to use terracotta to represent the passing of time and show the subtle changes that happens to people with time through gradations of mark and relief making. I can better illustrate and represent the condition of a woman, as a mother having given birth. And the earth is synonymous with Mother Earth.

Summer experience with a family of potters

“Each family member had a specific role in this production line. I took interest particularly to this lady; she was on the older side and yet she’s always cooking in the kitchen while decorating the ceramic plates. It also provoked certain thoughts in me about the distribution of family labour and the role of a woman in the household.”

Delia Prvački:

It was a summer holiday in 1967 when I met a family of potters. Every family member was a potter, hence they shared pottery as a passion. It was also their job with pottery being their family business. This family invited me and my siblings to their studio, and I was really fascinated to be there! A few months later I heard that a school was opening in another studio, which was the most famous traditional pottery workshop of Alexander Bogosi. And that’s where I spent the following two years. We had to walk about two kilometres from the main road to reach the studio and we would go there every week to make amazing pieces of works without many restrictions.

So, the person who ran the studio (the family of potters) was in his 70s at the time and had spent all his life as a potter. The moment he entered the studio, he would immediately sit down and work on his pottery wheel. It was not an electrical wheel; it was all manual. You have to turn the wheel with your leg. What fascinates me is the way that the whole family is involved in this production. He was spinning the wheel while his wife was finishing the products with decorations. After everything is ready, the family organises an outing to sell their work at the marketplace. Each family member had a specific role in this production line. I took interest particularly to this lady; she was on the older side and yet she’s always cooking in the kitchen while decorating the ceramic plates. It also provoked certain thoughts in me about the distribution of family labour and the role of a woman in the household.

The pottery wheel had always fascinated me, I never wanted to become a potter therefore I never mastered the skill. During my time at the studio, I tried and did some work on the wheel but eventually I didn’t develop a passion for it. I like to do everything by hand, and today I still do! Whenever I see him, this old man who had his hands full of clay, moving with so much confidence. He would endlessly turn the pottery wheel working his magic, and while his pieces were still half dry, he would apply colours on them. Then he would apply decorations. However, the decorations were not purposed to embellish to object, but rather it’s part of object’s body. The old man would also draw a line using a horn from a calf and thread a feather through it at the tip of the horn, where the slip colour would pass through.

So, he will put the slip of colour, and then with a fantastic movement and using only one hand, he will draw a spiral. And then stop to work on other things before coming back with a brush or the same tool, to mark around the line of the spiral. These markings will take the shape of a horn or of a blade of grass, which became the inspiration for my later works.

Regardless, this moment marked me forever. It was a powerful memory. And from that moment I got the idea of capturing time, the instance where eternity is captured.

Reflections on the political situation in Yugoslavia

“I started to work on this work, Danube, out of this necessity to deal with our destiny and faith. I was constantly thinking why we were in Romania and why we were on ‘the other side of the world’.”

Delia Prvački:

By the late 80s, the situation had started to become very tense in Yugoslavia, and it was worse in the Eastern bloc, eventually leading to the collapse of the Berlin Wall. And in Romania, we had a revolution at the end of December 1989. Just a few months earlier, I could not envision that this would happen.

I started to work on this work, Danube, out of this necessity to deal with our destiny and faith. I was constantly thinking why we were in Romania and why we were on “the other side of the world”. It felt like a punishment. I grew up with this idea that we were betrayed and given to the Soviet Union, who supervised us, ran our lives and controlled us. They did terrible things to intellectuals and artists. Censorship and persecution were something I grew up with. We were taught not to talk about them. That’s why I chose to do ceramics, because ceramics was not subjected to censorship.

Being in applied art was not the same as being a Fine Arts student, like being a painter. When you’re a painter, and when you do exhibitions, a group of security would come to check on your work and make comments like, “Why is this like that? What do you want to say?”

For me, doing ceramics was an escape from this. I started to think, I wanted to keep quiet and not address anything that is important. And the idea of representing the two walls on both sides of Europe manifested. The Danube River starts in Germany’s Black Mountains and goes through Europe and ends my country at the delta of the Danube River and finally flowing into the Black Sea. The work shows the symmetrical but opposing ideologies in the region. The landscape it is traversing is changing. It is a succession of images which follows the history of the political regime, symmetrical but contradictory.